THE BREAST CANCER MEME days AND THE LESSONS OF BLACKOUT TUESDAY.

Ugh. I just cannot. Well, I can.

I actually have a lot of words about this.

Way back around October 2010, I sent a private message to my friend Gabby asking her ‘what the hell was up with these Facebook statuses – do you know anything about it?’

“Say the color of your bra so the boys get confused. Don’t tell them what it means!”

Erm… how about no? What is the point..???

It wasn’t grassroots activism.

It wasn’t education and awareness.

It was a game.

I wasn’t moved to philanthropy or awareness or even donating my dollars by sharing my bra color, because I had no idea it was supposed to be about breast cancer awareness.

When awareness goes viral without actually saying anything…

These vague memes were shared millions of times and praised as “raising awareness.” Revisiting the memory of the occurrence through the case study in Strategic Social Media: From Marketing to Social Change ,alongside some additional deeper dives, truly highlights how diffusion without mobilization becomes a sort of “slacktivism” – symbolic participation with no real-world impact.

Remembering the few years of the Facebook meme also found my thoughts traveling towards a more recent cyberactivism issue – Blackout Tuesday – which happened during the height of the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor protests.

I’ll definitely touch more on that in a moment, but both of these viral social media occurrences show how easy it is for well-intentioned cyberactivism to slide into confusion, misinformation, and even harm.

Why the Breast Cancer Meme Went Viral

The original meme had three ingredients to make this recipe spread:

- PERSONALIZATION

Post your own bra color. Share where you “like it.” State your “number of inches.” Participation was easy, playful, and felt socially rewarding. - EXCLUSIVITY

“Don’t tell the men.”

Secrecy = instant community. You were “in” on the inside joke. - EMOTIONAL ALIGNMENT

People assumed it was for a good cause, even if the messages said nothing about breast cancer. And for those who did know the intention, posting felt like a morally aligned gesture… despite costing nothing and doing nothing.

Where the Meme Failed: Awareness vs. Knowledge vs. Action

It raised “awareness” of the meme… but not necessarily breast cancer.

People googled the meme, not how to perform self-exams or where to donate.

Hill and Hayes’ case study found many respondents to describe the attempt as counterproductive, misleading, or even offensive.

❌ It sexualized a disease that survivors describe as traumatic, painful, and lifelong.

❌ It deliberately excluded men, despite thousands of men being diagnosed annually.

❌ It substituted real action with a symbolic gesture.

Journalist Sonya Sorich seemed to share my thoughts on the viral posting, where awareness replaces real impact.

It seems vastly different than the abrasive, yet powerful efforts of the #fxckcancer hashtag on socials, and those bracelets floating around from Spencers. It’s bold, emotionally charged, and still direct, educational, and action-oriented.

Blackout Tuesday as a Modern Parallel

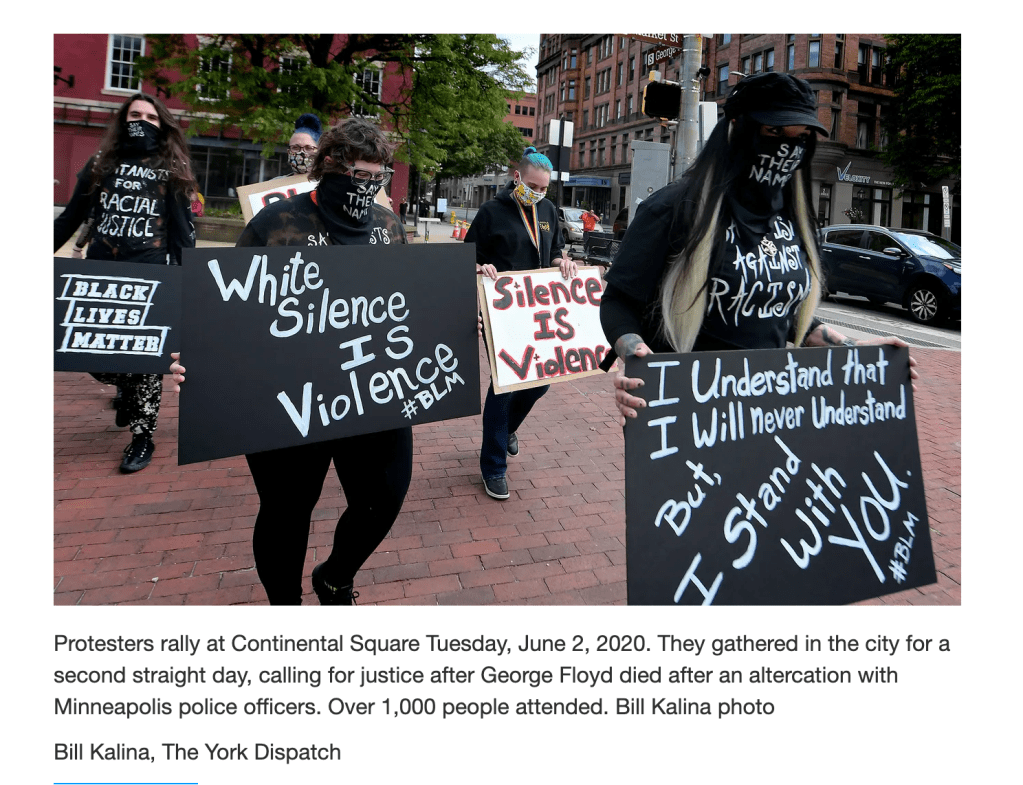

Because the breast cancer meme isn’t an isolated case, we saw a near-identical dynamic during Blackout Tuesday (June 2, 2020).

Millions of Instagram users (especially well-meaning white allies) posted black squares using #BlackLivesMatter.

The intention:

“Silence ourselves to amplify Black voices.”

But the outcome…

The #BLM hashtag became unusable for organizing, as activists tried to share urgent safety info, legal aid, protest locations, and other urgent and relevant information on the platform. Only to have the feed flooded with blank squares devoid of anything useful.

The Similarities of the Breast Cancer Meme:

- Both spread rapidly through social networks due to social pressure and moral signaling

- Both used ambiguous communication that required insider knowledge

- Both unintentionally obscured critical information

- Both gave participants moral “credit” without meaningful engagement

The Differences

- Breast cancer memes sexualized and trivialized the topic

- Blackout Tuesday unintentionally interfered with life-saving mobilization during an active crisis

- The emotional stakes were immediate and visible: police violence, public protests, national trauma

Within hours of Blackout Tuesday going viral, activists publicly begged users to stop using the #BLM hashtag because it was overwhelming real protest content. Confusion, fear of “doing the wrong thing,” and messaging contradictions left many feeling paralyzed to real action, much like the breast cancer memes.

NBC reported Blackout Tuesday became a teachable moment about the limits of symbolic solidarity for allies.

What this reveals about Mobilization vs. Virality

When we compare the Facebook breast cancer memes with Blackout Tuesday, a pattern emerges:

⬛️ VIRALITY requires novelty + emotion + low effort

The memes did all three.

⬛️ MOBILIZATION requires clarity + education + action steps/call to action

The memes did none of these.

Mobilization is defined by behavior change. Like showing up. Volunteering, donating, signing petitions, writing letters to public officials… Showing up.

The breast cancer memes didn’t mobilize.

Blackout Tuesday, in many cases, hindered mobilization.

Hill & Hayes argue that public health campaigns must distinguish between:

ATTENTION

AWARENESS

KNOWLEDGE

ACTION

and… align objectives accordingly (not confuse attention with impact). Most viral trends never make it past step one.

The Role of Real-Life Experience in Mobilization

We are reminded that emotional, embodied, real-life experience is the strongest trigger for meaningful mobilization. Again, mobilization moves you towards:

- Volunteering at a treatment center

- Donating to a verified fund/nonprofit

- Attending a protest

- Supporting legislation (or speaking against it)

- Sharing survivor stories

- Amplifying experts

- Connecting people to resources

These are actions that create lasting behavior and identity change – far beyond posting the color of your bra or where you sit your purse.

Symbolic action only works when it leads to real action.

When it replaces real action, it becomes harmful.

Choose Meaning over Meme Culture

I challenge us as marketers – both communicators and human beings – to ask:

- Does this message educate?

- Does it mobilize?

- Does it empower?

- Does it clarify or confuse?

- Does it create visibility or drown out crucial information?

Our greatest responsibility in social media is not to chase viralty. We’re here to cultivate ethical, informative, actionable communication that respects the gravity of the causes we claim to support.

When we choose clarity over secrecy, education over innuendo, and action over symbolic gestures, we move from slactivism toward meaningful community driven impact.

Add to the conversation